- How do we shape our ability to critically evaluate the credibility of information available online?

- How do we represent ourselves online?

This is a tricky question. As with some of the other reflection questions, it is difficult to answer because it requires such generalizations. From the data, it does seem that youth seem less concerned with revealing information about themselves than adults do. Whether this is merely comfort with a newly emerging sense of publicity or naïveté remains to be seen. Until we are 20 years down the road and we have a president elected who had drunken frat boy pictures or scantily clad bikini pictures in Facebook from high school and college will we know whether society is truly moving past our current fear of impropriety.

As I pondered implications of the research in these articles, I kept thinking about the online entries of one of my friends on social media. I was compelled to go back through her feed and take note of some of the phenomenon noted in the articles. I will attempt to share some of them as they apply throughout my reflection.

Creating who we are...

From the research in these articles, it would seem that youth are more conscious about what they put online than one might first think. For example, according to Stern (2008), “Performing and playing with their identities in online public spaces is especially gratifying, because it is viewed as less risky but potentially more validating than experimentation in other arenas,” (p. 113). I had not thought of this before, but it makes sense. If you make a misstep online you can always just say you were messing around - that it only took a couple of minutes. Play it off like you didn’t mean it and you hadn’t really invested in it, even if you had. When you make a misstep “live and in person,” it is harder to undo. Taking this further, Stern asserts that “instances of audience rebuke push young authors to consider how the acts of encoding and decoding messages can diverge from one another, and reveal how message creators in any context must work to insert meaning into their texts strategically," (p. 114). My friend definitely experienced audience rebuke several months ago when she posted several memes and thoughts following the Sandy Hook shootings and the gun control debate that followed.One of her posts that got the most negative blowback was comparing the Obama administration with Hitler and the Third Reich as they called for more gun control.

As you can see by the ending, the rebuking was noted but had not actually changed the behavior of my friend, it only changed how she framed her comments. However, she has posted fewer and fewer inflammatory things as time has progressed. Whether this is her taking note and trying to change her online image or simply ceding to propriety, one cannot be totally sure. However, she does seem to agree with the blogger who said, "just because you read my blog doesn't mean you know me," (p. 112) when she posted this:

Understanding the world around us...

"To prepare youth to make fully informed credibility decisions, they must become fluent in the tools that facilitate the conversation and become aware of potential biases in the network technology itself," (Lankes, 2008, p. 116).

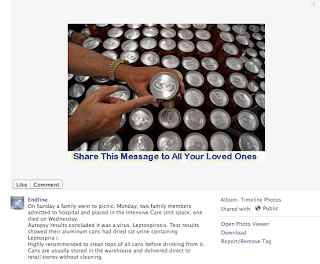

If you open the picture to see the story, you can see that it is about a family getting sick on a picnic due to rat urine on the soda cans. It took about 20 seconds to open up snopes.com, copy and paste the item, and find out that they only true part of the story is that indeed rat urine can cause the illness - but none of the examples given are even close to true. According to Flanagin and Metzger, "youth, particularly younger children, may be more susceptible to digital misinformation and less able to discern credible from noncredible sources and information than are adults who are more cognitively advanced," (p. 16) (emphasis original). However, as a user of social media, I can tell you that, despite the authors' assertions that it is youth that suffer from their lack of experience and cynicism, there are many adults out there who gladly pass along information like this without critically examining its credibility. Teaching kids to be critical and skeptical without completely disbelieving everything needs to be at the heart of our comprehension skills instruction - right next to learning how to infer.

Tangled...

I think the scariest part of the internet is something that not enough youth think about - the idea of how tangled we are in cyberspace beyond our own ability to know. In some ways it reminds of the story of Brer Rabbit and the Tar baby - where he keeps hitting the tar baby over and over and getting more and more tangled as he does. This is what is happening to us the more we use the internet, particularly social media. Once a piece of us is in cyberspace, we lose control over what happens with that piece. Much like celebrities who are affected by the news in the tabloids whether they personally read them or not, "when young people become the subject (or object, if you will) of digital media, they are used by it; when a digital media artifact—a digital media file of any type, for example video, audio, still image, text—that features them is created, part of them becomes entangled with the digital media and forms the substance of it," (Heverly, 2008, p. 199). This idea is the purpose behind this PSA:

I think that many students don't really think about this side of the equation. They are thinking about looking cool and wanting their friends to notice them. They rarely think beyond their immediate circle to a broader audience because they can't really fathom that someone else might be interested. When it comes to what we need to teach our students, I think this is possibly the most important lesson.

References

Heverly, R. A. (2008). “Growing Up Digital: Control and the Pieces of a Digital Life." In McPherson, T. (Ed.) Digital Youth, Innovation, and the Unexpected Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Lankes, R. D. (2008). Trusting the Internet: New Approaches to Credibility Tools. In Metzger, M. J. and Flanagin, A. J. (Eds.) Digital Media, Youth, and Credibility. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Once posted, you lose it. (2008). Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CE2Ru-jqyrY&feature=youtu.be

Stern, S. (2008). Producing Sites, Exploring Identities: Youth Online Authorship. In Buckingham, D. (Ed.) Youth, Identity, and Digital Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment